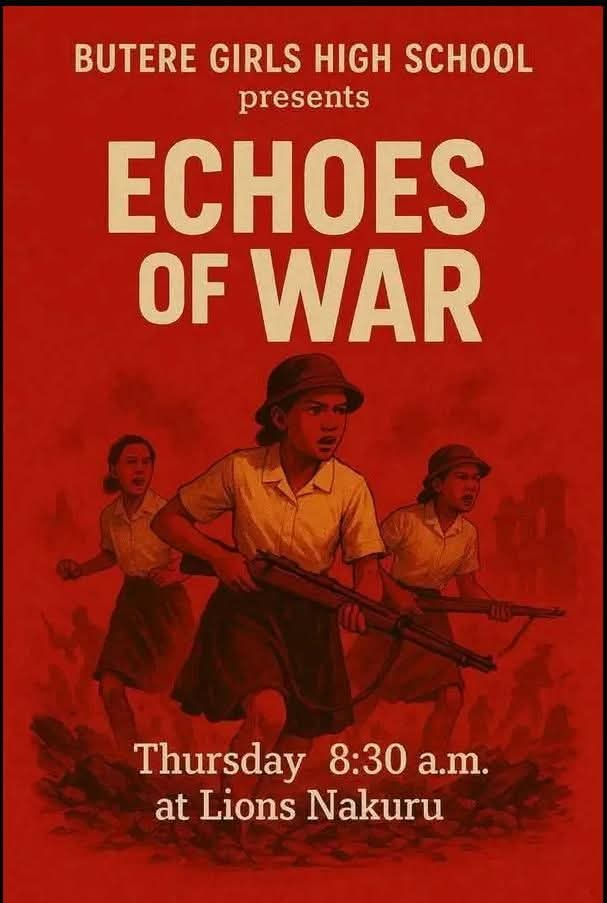

I did not sit in the grandeur of a theatre to watch Echoes of War, the latest dramatic production by Butere Girls High School, but I listened and in listening, I heard both its brilliance and its flaw.

Scripted by former UDA Secretary General Cleophas Malala, Echoes of War is unmistakably brave. It charges at the heart of political betrayal with the raw anger of a disillusioned citizenry. It is bold, perhaps too bold for its own literary good.

At its core, the play attempts to ridicule a government it sees as deaf to the cries of its people. The narrators, without mincing their words, thunder early on:

“Even a five-year-old child can tell that these empty promises are a scam.”

The sound effects, bombs exploding, gunshots echoing, drag the audience into the recent Gen Z protests that shook Kenya. The play wants to be a mirror of this moment in history. And that is exactly where its power and its weakness lie.

The central character, Zakayo, is drawn too close to reality, a thinly disguised representation of President William Ruto. In fact, it’s not even disguised. It is direct, it is loud, and it leaves nothing for the audience to interpret or imagine. At one point, the narrator cries:

“Zakayo must go!”

And in that moment, Echoes of War departs from literature and lands straight into activism.

This is where, as a lover of literature, I feel the play could have done better. Art, especially theatre, thrives on the power of suggestion, on the delicate weaving of metaphor, on the sophistication of symbolism. Direct attacks may win applause in the heat of the moment, but subtlety wins immortality.

I think back to plays such as Kifo Kisimani by Kithaka wa Mberia, which critiqued power without mentioning a single name. Its characters, Mutemi Bokono, Mwelusi, and others, were faceless masks of tyranny. The beauty of such writing lies in its universality; a play like Kifo Kisimani could be set anywhere, at any time, and still capture the essence of a government gone astray. It is this kind of writing that transcends the moment, outliving the politicians who inspire it.

Similarly, Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s The Trial of Dedan Kimathi is a fine example of theatre that speaks truth to power without ever calling out specific individuals. It uses the figure of Kimathi as a symbolic representation of resistance against colonial oppression, but the play’s larger message about the abuses of power is applicable to any regime, in any era. Its power lies not in the names it mentions, but in the universal themes of justice, struggle, and the cost of freedom.

In Shreds of Tenderness, Ugandan playwright John Ruganda captured the painful aftermath of dictatorship, but again, without naming names or casting blame on a specific ruler. The play’s subtle examination of the impact of political violence on families allows the audience to see the emotional and psychological scars left behind, without resorting to political slogans. It is the sort of play that lingers in the heart, long after the final curtain has fallen, because it makes us confront the reality of living in a fractured society.

But Echoes of War? It is tied too tightly to Kenya’s present-day politics. Its anger is fresh, but freshness does not always guarantee relevance tomorrow. When political tides change, when Zakayo becomes a name lost to history, what then remains of the play?

Art should outlive the headlines. Great plays do not age with presidents — they endure with people.

However, in the context of Kenya’s political landscape, this play might not be received well by the government. Malala, who penned this searing critique of leadership, is not a stranger to controversy. His recent fallout with President Ruto, following the impeachment of Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua, casts a long shadow over the play’s reception. The timing is sensitive and the government may view the play not as a work of art, but as a provocative act of defiance. In such a climate, the play’s reception could be less about its artistic merit and more about its potential to stoke political flames.

That said, I cannot fault Butere Girls High School for their courage. In a world where school drama festivals are often tamed, where students are taught to play safe, their decision to confront power deserves recognition. But courage alone does not make a great play. Craft does. Symbolism does. The ability to critique without becoming a political rally does.

Echoes of War burns bright but like a matchstick, it risks burning out just as fast.

In future, one would hope that playwrights like Malala, with their rich understanding of the stage, would choose the timeless path — to wrap their criticism in the cloth of creativity, to let metaphor do the heavy lifting, and to trust the intelligence of their audience.

Because when all is said and done, it is not the loudest play that lasts — it is the wisest.

Facebook Comments