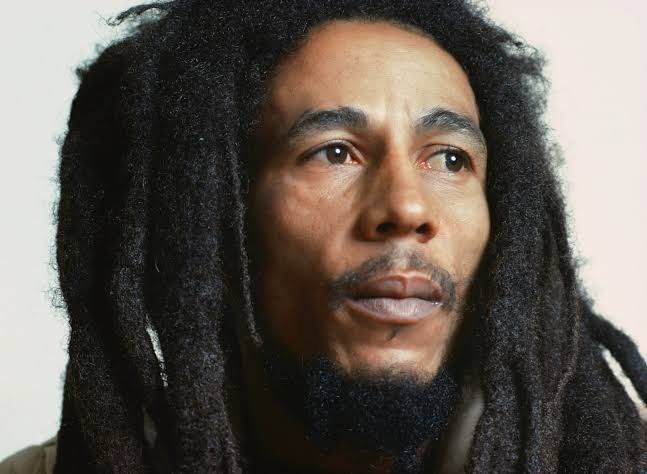

Some songs never age. Some voices, even in death, never fall silent. And some places, humble and almost invisible to the rest of the world, become sacred keepers of legends. Forty-four years have passed since Robert Nesta Marley, Bob Marley, breathed his last, yet his spirit still hangs in the air like a familiar scent. For me, it lives strongest not in a record shop in Kingston, nor in a concert hall in London, but in a dusty, creaky old building at the heart of Isongo village market.

That building once belonged to the late Mwalimu Nanzushi, one of the last old school teachers whose chalk-stained hands shaped more than just young minds. It was a rectangular block with flaking blue paint, a sagging tin roof, and a narrow wooden door whose hinges sang like an old tune. Tucked in the left corner of that row stood a Kinyozi, not grand by any measure, but full of soul. We simply called it “Kwa Chris.”

Chris was the eldest of three brothers who ran the barbershop, alongside Humphrey and Nathan. Together, they turned that tiny space into a kind of shrine, not just to grooming, but to sound. Their love for reggae bordered on the sacred. They didn’t just play Bob Marley, they summoned him. They resurrected him with every needle drop, every twang of bass, every cry of guitar, every word that rolled out of that tin-roofed haven like incense from a censer.

This was the early 2000s, when village life still pulsed with radio, rumour, and rhythm. Back then, Isongo’s teenagers, myself included, treated haircuts like weekly pilgrimages. But truth be told, we didn’t just go to shave. We went to listen. We went to feel.

Bob Marley’s voice filled the room before you even entered. It greeted you at the door like an elder. From War to No Woman No Cry, Africa Unite to Natural Mystic, the songs didn’t come as entertainment but as philosophy, simple, yes, but searing.

Inside, cracked mirrors and peeling posters of Marley, Haile Selassie, and other dreadlocked prophets lined the walls. The floor was never quite clean, but the sound was pure. Chris, with his wide forehead and serious face, would shave your head like he was sculpting it for battle. And just as the machine buzzed close to your ear, Bob’s voice would soar; “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery…” and your skin would prickle.

There was something holy in that place. No one shouted. No one quarreled. Even the little boys playing football outside lowered their voices when they passed. We believed the Kinyozi was protected by the rhythm pulsing through it.

Today, that building still stands, tired now, leaning slightly, like an old man who has outlived his time. The brothers have since moved on; Chris now drives for the County Government of Kakamega, I’m told. Humphrey runs a clothes business. Nathan is busy too. The music system is long gone. The turntable, once treated like a sacred drum, probably lies rusting behind someone’s house.

But memory has its own speakers

Sometimes, when I pass that spot, I still hear it faintly, like a dream revisiting a body. The thump of bass, the scratch of vinyl, and Marley’s eternal question echoing through time: “How long shall they kill our prophets while we stand aside and look?”

Bob Marley died on 11 May 1981. But what is death to a voice that made itself at home in the hearts of men and in the corners of rural Kinyozis? He may have left the world at 36, but his spirit is threaded into the hairlines of generations, the rhythm of matatu rides, the crackle of village radios, and the lilt of young men whistling One Love as they balance sacks of maize on their heads.

In Isongo, his dreadlocked shadow still dances in silence. It watches over the children who now sit where we once sat, unaware of the history beneath their feet. And for those of us who remember, the rhythm plays on, not in our ears, but somewhere deeper.

Forty-four years on, Bob Marley remains, in a quiet Kinyozi, the patron saint of song, soul, and shaved heads.

Facebook Comments