It was one Saturday afternoon, sometime last year, when I bumped into my friend Parto. Yes, Parto, as we fondly call him. He was walking through Kakamega town, balancing what looked like an entire shelf of books on his right arm. It was an odd sight. Naturally, I was curious. Where could he possibly be taking all those books on a weekend?

He looked tired of them. “They’re just taking up space in the house,” he said casually. “Too much clutter. I need to get rid of them.”

I blinked. Since when did books become a burden? When did knowledge start feeling like clutter?

Trying to stay calm, I asked him,

“We Parto, unapeleka wapi hizi vitabu zote?”

He replied, “Nafikiria kumpatia Musungu. Nilikuwa nataka kuzitupa, lakini nikakumbuka Musungu ni fan noma sana wa vitabu, especially books za zamani.”

Now, Musungu is one of my comrades here in the streets of Kakamega. A Rastafarian with long, threaded beards who has never wavered from the lifestyle. Musungu is famous, even notorious, for quoting from ancient scriptures, rare philosophy texts, and spiritual books whose titles most people have never heard of. These conversations usually happen at our regular gathering spot, Bunge la Wananchi

Bunge la Wananchi isn’t just a baraza. It is an open air university of sorts, a place where thoughts collide, where ideas are grilled, and where truths are spoken with no fear or favor. Located beside a humble kinyozi run by Musungu, Nyayo, and Juma, this space has hosted debates ranging from politics and religion to women’s rights and the struggles of ordinary citizens. In Kakamega, as in many Kenyan towns, Bunge la Wananchi is where the street intellectuals sit. Those who may not wear suits but carry libraries in their minds.

So I didn’t waste time.

“Nipatie angalau viwili kabla Musungu hajafika,” I pleaded.

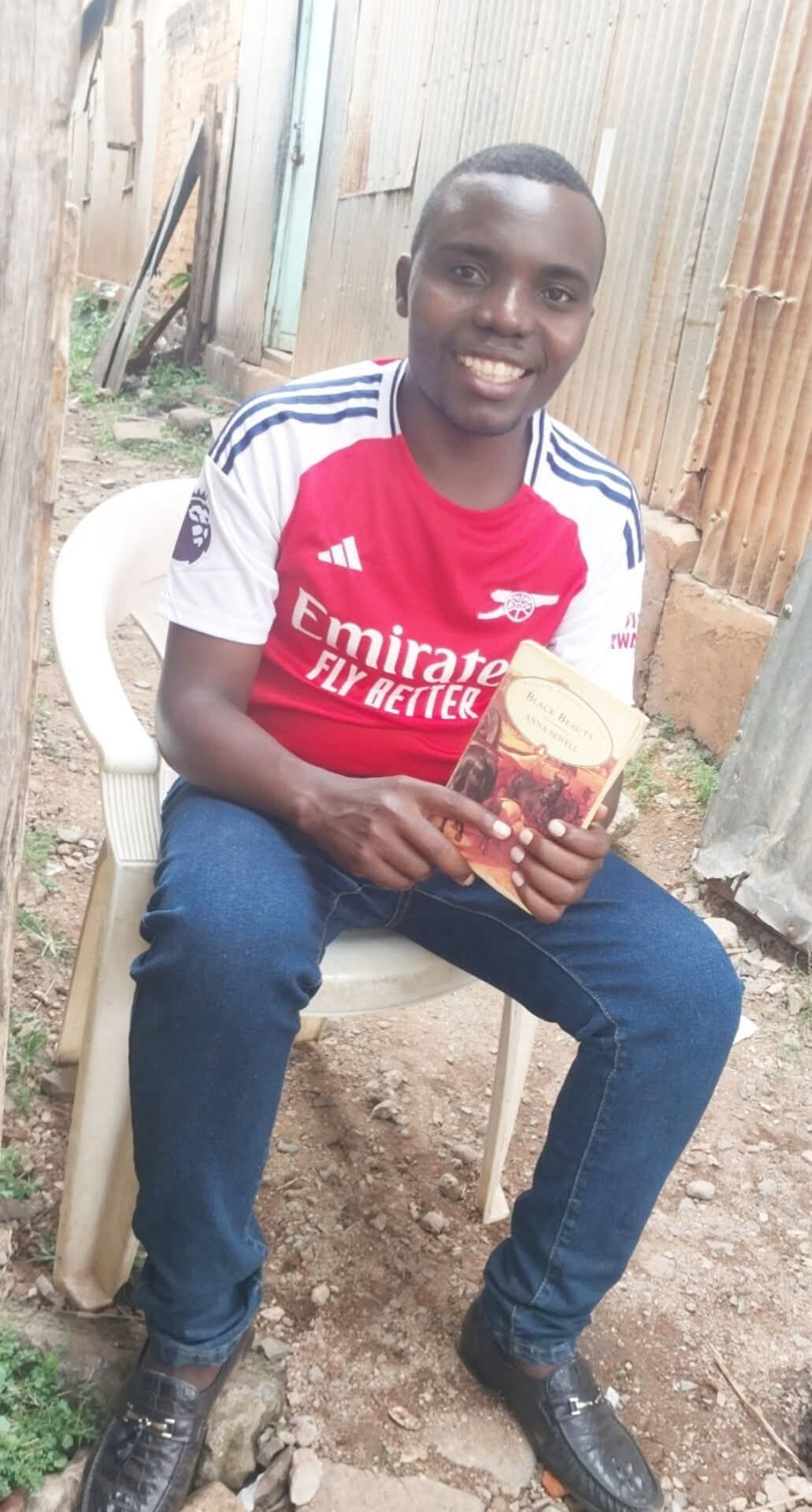

He hesitated, then slowly reached into the pile and pulled out Black Beauty by Anna Sewell.

“Chukua hii,” he said. “Hizo zingine lazima ziende kwa Musungu.”

I smiled, nodded, and said, “Asante, mkuu.” That was enough for me.

That evening, I began reading. Slowly at first. But before long, I was deep inside the world of Black Beauty, a horse with a voice, a soul, and a story that could humble any human being.

First published in 1877, Black Beauty was written by Anna Sewell to promote the humane treatment of horses in Victorian England. But it is more than a tale about animals. It is a timeless mirror into human behavior. The horse’s story, told in first person, chronicles the highs and lows of being passed from kind to cruel owners, of being used, abused, and occasionally loved. Reading it today, in this part of the world, the metaphors feel strikingly familiar.

As I turned the pages, I started seeing the world around me with new eyes. I thought about the boda riders we shout at when they delay us. The street children we ignore. The elderly we grow impatient with in queues. The junior officers we look down upon at our workplaces. Those we dismiss, or overlook simply because of their titles. How often do we, like some of the owners in Black Beauty’s life, treat others as burdens instead of beings?

There is a moment in the book when Black Beauty is passed from owner to owner, some gentle, some violent. With each transfer, he carries not just his load but emotional weight. That struck me deeply. Life too throws us into hands we do not always choose. Sometimes we are cared for. Sometimes we are simply used. But like Black Beauty, we keep going, quietly, with resilience, and often without thanks.

I finished the book in February this year. But its voice lingered. It had spoken to something within me. And earlier this month, I picked it up again, not to reread, but to re-feel.

That is when it hit me. Some books do not just tell a story. They watch you back. They see your flaws. They whisper your truth. And they leave you changed.

And perhaps that is why we need spaces like Bunge la Wananchi. Spaces where books, thoughts, and life intersect. Where even what others discard can become something precious. Something transformative.

Looking back, I don’t think Parto knew what he was giving me that day. He didn’t just hand me a book. He handed me a mirror.

And that mirror, disguised in pages, dust, and a horse’s voice, is something I will always carry with me.

Facebook Comments