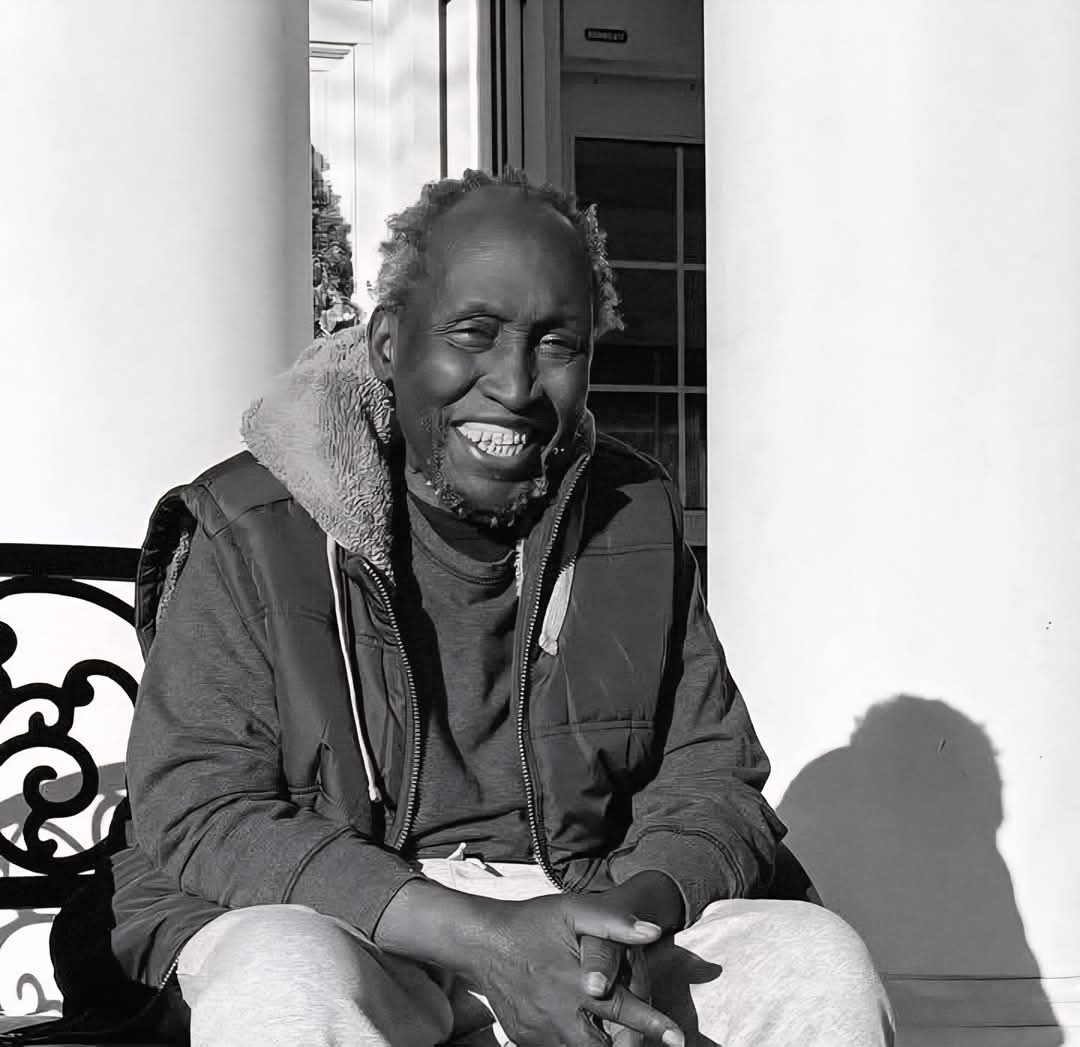

I never met Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. I never sat in a lecture hall to hear his voice echo across the walls of a university theatre. Yet I knew him. Deeply. Intimately. I met him again and again not in flesh but in the pages that lit the fire of literature within me, in the words that taught me what it means to be free, to be African, to remember.

It all began in a small classroom at Shikomari Mixed Secondary School. A place far removed from the polished floors and book-laden shelves of city academies. We had no library. Not even a dedicated reading corner. But we had something greater—hunger. A raw, unyielding hunger for knowledge, for meaning, for stories that told the truth about who we were.

In that world of scarcity, books were sacred. They weren’t objects, they were events. If you wanted to read, you didn’t look for a shelf. You looked for a person. For us, that person was Madam Mildred Olwenyo.

Madam Olwenyo was more than an English and Literature teacher. She was the living embodiment of the texts she taught. Short in stature but towering in authority, she moved through the school with the confidence of someone who knew that words could shape nations. With her firm voice and graceful presence, she ruled her small literary kingdom with a quiet, dignified power.

Her books were few but fiercely protected. Approaching her for one was no casual act. She would glance at you, eyebrows slightly raised, and ask, “Do you love literature or are you here to waste its time” That question wasn’t a warning. It was a challenge. And for those who passed it, she became the most generous custodian of stories.

When I finally earned her trust, she placed in my hands Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Weep Not Child. That moment changed everything.

Through Njoroge, I wandered the tremulous corridors of Kenya’s colonial past. I felt his hope, his fear, his longing to dream in a world that punished dreamers. Ngũgĩ didn’t write with flourish. He wrote with fire. His words were simple, but his truths were seismic.

Later came The River Between, and then A Grain of Wheat. Each text a deeper baptism into the history we were never taught fully, the dignity we were taught to doubt, and the resistance we were meant to forget. Ngũgĩ did not entertain. He enlightened. He was not just an author. He was an awakening.

By Form Three, I had become a regular visitor to Madam Olwenyo’s sacred book trove. Another student who shared my literary hunger was Laureen Chitechi. Brilliant, thoughtful, and always ready for a spirited discussion about characters, metaphors, or why Ngũgĩ used a certain phrase the way he did. We spent long hours under the trees after class, debating literature as though it were life itself.

Laureen is now a medic at the Kenyan coast. Just this morning, I called her not just to reminisce, but to ask her something that had quietly troubled me. I couldn’t quite remember the first name of our beloved Ms Olwenyo. Without hesitation, Laureen laughed and said, “Mildred. It was Mildred Olwenyo.” Her voice, warm and precise, carried a musical Swahili accent now shaped by the ocean breeze and years of serving others in clinics far from our rural school. In that moment, I realized how deeply those classroom bonds had endured, and how literature had stitched them into permanence.

And it wasn’t only Ngũgĩ who shaped us.

We were tested and tempered by texts like Coming to Birth by Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye, where we followed Paulina through pain and transformation as Kenya itself was reborn. We pondered the brevity of life and the power of perception in Naguib Mahfouz’s Half a Day, and we explored the emotional wreckage of war in Shreds of Tenderness by John Ruganda.

Even the Elizabethan drama of The Merchant of Venice found resonance in our village voices. We debated Shylock and Portia not just as students of Shakespeare, but as young Kenyans grappling with justice, mercy, and the weight of identity.

These texts weren’t just syllabus requirements. They were portals. They introduced us to voices our textbooks skipped, emotions our parents rarely named, and truths that history exams refused to grade. Through them, we found clarity. Through them, we found ourselves.

But always, it was Ngũgĩ’s voice that rang loudest.

Years later, reading Decolonising the Mind, I finally understood the power of his choice to write in Gikuyu. It wasn’t rebellion. It was reclamation. A conscious return to self. He reminded us that to speak in our mother tongues was not backward, but brave. It was the first step toward freedom.

That truth still stirs in me today.

Maybe one day I too shall write in my local dialect, Luhya.

Maybe one day I will let my mother tongue shape the lines of a poem, the rhythm of a story, the spine of an argument. Not for exoticism, but for honesty. For memory. For belonging. Because, as Ngũgĩ taught us, when we reclaim our language, we reclaim our souls.

And now, as I reflect on his passing, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, gone at 87, I do not mourn a stranger. I grieve a mentor. A teacher who never knew my name but shaped my thinking. A revolutionary who never picked up a weapon, yet taught us all to fight with memory, with language, with truth.

Ngũgĩ sat in the back of my classroom at Shikomari, not in person but in spirit. In pages. In the eyes of Madam Magret Olwenyo, who handed me the torch and said, “Read.”

And I did. I still do.

Because Ngũgĩ is not gone. He is sown like seed. And his words keep blooming wherever young Africans dare to read.

Facebook Comments